What turns a good idea into you going on stage?

When you apply to a call for papers — also known as CfP — for a conference you want to speak at, your submission is your business card. Unless you're already well known in the public speaking context, that is the only factor a group of strangers will use to decide whether your session should take up one of the scarce slots at the event. An abstract can make it or break it for your chances to be picked — yes, even if you are already well known!

After serving on conference committees for a long time and reading thousands of submissions, I have come up with a list of things that work and missteps to avoid. They may sound obvious, but every year there comes a time when I wish someone thought of them before submitting.

Of course, other committee members and organisers may be looking for different things; I can't promise that following them will be enough to get through. I can't claim that I speak for anyone else other than myself, either. I just hope this set of guidelines will help folks write better submissions that have better chances in the ultra-competitive world of conference speaking.

You may see successful abstracts that don't follow some, or even all of these guidelines, but their success is likely due to other factors, and exists despite the failings in the submission. In my experience, these are the exceptions, not the rule.

Before you start: the idea

The first step is, obviously, figuring out what your talk will be about. A boring or unoriginal idea will not get you very far, even if everything else is perfect. When in doubt, try asking friends and colleagues whether an idea you had is interesting to them!

You want a topic that is:

1. Original

When you enter a call for papers, you are essentially joining a competition to win a scarce resource: there are always more submissions than available slots in a conference schedule. The more original and interesting your idea is, the more chances it has to make it through the selection process. More “in vogue” and common-place topics will have a tougher life in the CfP, because of the bigger competition they face.

This doesn’t mean you have to find a completely new and never-before-seen thing to talk about — even common topics can become interesting if you bring something more you to them: can you offer a unique perspective? Is there new insight, process, or approach you can cover? Excellent!

People are more engaged by stories than by dry, technical sessions where you enumerate a series of things. Anything with a compelling narrative around it is more likely to make it through. Why are you talking about it? Is it something you've faced/worked on? Is there any war story you have on the topic? Any learning to share that can save others time and pain? People can read the documentation by themselves; your job is to convince them it's something they may wanna do.

Lastly, keep in mind that committees tend to prefer new talks over ones you've already presented a number of times. This is especially true in the Android community, where most conferences make the recordings available for free a few months after the conference. "Reheated" talks will only get you so far! It's fun and exciting to speak at conferences, but you don't have to be at all of them. You may be a great speaker and have great sessions, but if you have nothing new to say, you should also consider leaving room to others.

2. Timely and relevant

Covering old technology is ok if there is a good reason for it, but timeliness is fundamental, especially for entry level sessions. An introductory talk on a piece of tech people have known about for years is not interesting to anyone. Remember that advanced topics can have a longer shelf life, but they might only be interesting to a smaller part of the audience, so striking a balance is important. A great talk has a broad appeal, even if it is an advanced topic.

Something that always gets me as a committee member is how some folks submit sessions that aren't relevant to the conference. Professional speakers are the main culprits, sending completely random proposals that will never, ever be accepted at a technical conference. I have, however, seen tech folks also doing that sometimes.

Don't. There are literally zero chances your talk will be selected if it's not deemed to be interesting to the audience. Don't fall into the sunken cost fallacy, and don't fall in love with your ideas before they prove themselves. If it feels hard to make an idea relevant to the audience, it's probably because it's not. You'll have better luck with a different topic!

If you are assigned a sponsored slot and want more people to come to your session, make sure your talk is not just marketing for your product or company. You could submit sessions about processes or third party tools that help you, or show off aspects of the cool stuff you work on that are applicable to others as well. People will like it!

3. Plausible and focused

We often get multiple sessions covering a topic we'd like to have; at some point we have to select one. If you have expertise on a topic, for example, because it's something you've previously discussed in public, or written about, that will surely play in your favour. It's not mandatory, to be clear, but it is more important the newer you are to public speaking.

Another important trait is being focused. Don't put multiple semi-related topics into the same abstract. If you feel like your main topic doesn't give you enough material for a full session, consider a lightning talk format; if instead you feel each topic stands on its own, and could be its own talk, submit separate sessions for each. Consider the format you're choosing, and how plausible it looks you'll be able to cover everything you mention in the allotted time. Don't forget the session duration includes audience questions!

A lightning talk is unlikely to be able to cover multiple topics, even at an extremely introductory level. Lightning talks are also unlikely to be able to go into much detail, unless they are laser-focused on a minor aspect. But don't be afraid of making more introductory talks — people who are new to the topic will enjoy a gentle introduction more than being thrown into the deep end. Not all talks need to be a deep dive.

Recap

Let's write an abstract

You have an idea that you think can work out, it's now time to write it down and submit it to the CfP. Let's see what can increase — or horribly hinder — your submission's chances of success.

1. Just the right length

It's important that your submission is just the right length. Writing an excellent abstract is not easy, as you need to strike a delicate balance between being exhaustive enough for people to understand what the session is about, and leaving out enough that they're not intimidated by it.

Think about how the committee will perceive your abstract. Too short, and you'll give the impression you're not even trying; too long, and they may end up just skimming it. Let's be honest here, when you have hundreds of submissions to go through, walls of text are annoying. On the other side of the spectrum, one-liners are also instantly a no-go.

There is no hard and fast rule on exactly how long an abstract should be; I normally have two or three paragraphs in an abstract, each made up of a handful of sentences. In a three-part abstract, I find it helps if each paragraph has its own goal:

- The first paragraph is the setup: name the topic, and explain why the reader should care, why the audience should care

- The second paragraph touches on some of the finer points that will be in the session, and serves as a high-level table of contents. This lets people judge by themselves if the session is relevant to them

- The last paragraph is a brief list of the main takeaways the session will provide, reminding the audience why they should attend

If the conference provides a field for notes to the committee in the submission, use it to communicate any extra information you think is relevant (e.g., a full table of contents, additional context on the topic, etc). Don't use it for writing cover letters or providing irrelevant information. It is perfectly ok not to write anything at all if there is no need to.

2. Get people interested

Vaguely worded abstracts aren't very interesting. Committees understand that the talk doesn't exist yet and some details will be in flux until you get on stage, but your abstract must convey that you have a pretty good idea of what you want to cover and how. Committees will choose submissions that show you have a plan.

Make sure that your abstract mentions some examples of what you'll cover in the session: technologies, techniques, processes, APIs. As a rule of thumb, ask yourself: if it were someone else doing that talk, what would I want to see mentioned to convince me? People will end up skimming abstracts that intrigue them from the conference schedule, and having some relevant keywords in there can solidify their intention to attend a session.

Point out to the audience what the main learnings are: processes, stories, APIs. It doesn't have to be a bulleted list, but you should convey the actual value proposition and set expectations. Be specific, avoid platitudes, get to the point. The goal is to entice the committee and audience, not to be exhaustive. The abstract should not feel as long as the talk.

When it comes to categorising your session, remember that all formats and levels have equal dignity. Don't default to a higher level than necessary just to look smarter — it is counter productive. If your topic fits in a smaller session, go for it. Nobody likes homoeopathic sessions where the content is so diluted it's not even there anymore.

The title is also very important. Puns and witty wordplay are great... until they aren't. Don't stretch jokes and memes too far to fit your talk; you risk becoming cringe-worthy. The title is what people will form their first impression of your submission from. Make it short, to the point, memorable, and indicative of what's special about your session.

3. Form and function

You would be surprised by how many submissions come in badly written, containing typos, or in broken English. Put yourself in the shoes of the committee, who are probably people that don't know you: how confident can they be in the session being a success, if even the abstract has typos and bad grammar?

While this disadvantages non-native speakers, remember that you can — and should! — get folks to help you with the abstract. I get it, I am not a native English speaker either. Regardless, having no typos and mistakes in your submission remains the baseline for acceptance. Speaking is much more difficult than writing an abstract, especially with the added pressure of being on stage, and we know it. Before submitting, consider using tools like Grammarly, Grazie, and Google Docs to help you proofread and catch any mistakes. LLM tools such as ChatGPT and Bard can be used for proofreading, too, but always take their output with a huge grain of salt.

Beyond basic grammar, the tone of voice is also very important. You have a lot of freedom there, but there is something to absolutely avoid: marketing speak. Long, complex sentences full of fancy words and enthusiastic adjectives, devoid of all meanings, are a no-no. Focus on how people will perceive what you write. Would you want to go see a talk that feels like it was written by a used boat salesperson? If your submission uses words like revolutionise, I won't be able to take it seriously.

The same goes for facts, names and acronyms you mention in your submission. If you get a name, concept, or name wrong in the abstract, how likely are you to know it well enough to be able to present it? Always, always re-read your drafts before sharing them with your friends, and then again before submitting.

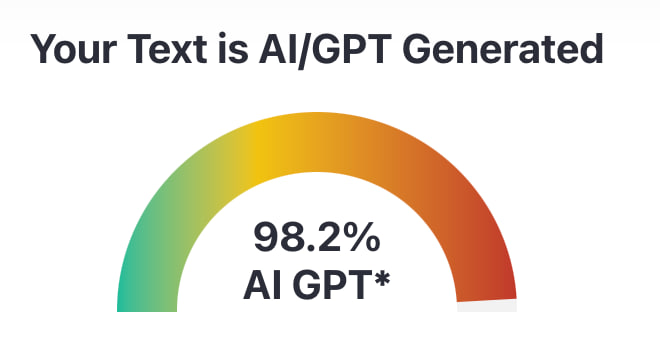

And one last thing: please do yourself a favour and don't copy-paste straight from ChatGPT, Bard, or any other LLM. They lack the required expert domain knowledge to write something meaningful, hallucinate facts, and aren’t great at writing abstracts to begin with. Of course as a committee member you can never be sure if something is LLM-generated, as there is no 100% reliable detection method, but it remains very easy to spot some cases of "the bot wrote this for me". The usefulness of these tools is lower than many think, given you essentially have to rewrite their output anyway, but if you feel like you need help to get started, or use them as proofreading tools, go for it.

Be mindful about it — if someone feels you can't even be bothered writing an abstract, they likely won't even bother reading it.

4. Get feedback

Speaking of getting others to help: it's very important to get feedback early and often. Just like you should validate your ideas with others, also make sure you run your draft sessions by people who can provide valuable, honest feedback.

Making sure other folks also like your idea, and your abstract, will help ensure it has the broadest appeal possible — and thus will more likely be picked. If you still feel unsure about your session after showing it to your friends, try to find someone to mentor you. You can ask other speakers, colleagues, or committee members to help you out!

5. Who are you?

While this isn't strictly about the abstract, it's important to think about the rest of the information you are asked to submit. Make good use of the bio field, too! The committee might not know you, and a good bio is key to providing them insights into what you do and what your relation is to the topic you submit.

Make sure you always mention where you work, and what you work on. Writing your role is useful as well, but don't fill it with things like "spoke at conference X", "participated in event Y", etc. These don't really add anything, and may even feel a bit desperate for attention.

Keep your bio up to date and make it relevant to the submission(s) you bring. The committee will be thankful for it, and that's always a good place to start from.

Recap

The long wait

Now that you have an idea you know can work, presented in an appealing way, and that your friends like, it is time to submit the session to one or more conferences. Open their call for papers portal, and send it.

Congratulations, you're done! I'm rooting for you! 🤞

Didn't get in?

Hopefully your submission will be accepted, but if it isn't, don't despair! There are other conferences your session may be better suited to. Don't take rejections personally. It may have not made the cut just because there were tons of other excellent submissions, which worked better within the constraints of this particular event.

Don't get discouraged. If you want, you can reach out to the committee to ask for some feedback. Keep in mind they may not have specific points to offer; unless there is something egregiously wrong with your submission, the most likely reason for the rejection is that there were tens of slots and hundreds of submissions. For more insights, look with an open mind at the sessions that were selected, and compare them with yours: were they different topics? Or more authoritative figures covering the same one? Or just better packaged?

In any case, don't give up! You never know which other conference may pick you, nor when.

Thanks to Maria Neumayer, Mark Allison, Daniele Conti, and Aurelio Laudiero for proofreading ❤️